The Historical background of Baulism in the 19th century

Colonial Bengal, particularly the rural zones, saw great turmoil due to massive changes in the socio-economic structure and the consequent rise and decline of various classes. Just as urban zones grew, such as Kolkata based on the colonial mercantile economy, rural areas saw impoverishment rise through tax oppression, forced cash crop cultivation and food grains trading that even caused a massive famine in 1770.

New revenue collection arrangements saw the entry in the rural areas of a new landlord class, many of whom were from urban areas, made money from trade, but were also educated and close to the British colonial rulers. The Permanent Settlement arrangement of 1793 introduced many new entrants to landlordism, but they had no experience in handling the task. Thus, the joint–colonial–local elite-based agro-capitalism project failed. However, it brought urban and rural networks closer and enhanced both interactions and turmoil in rural societies.

The situation was compounded by peasant unrest, which spread across Bengal as the older classes, ousted from power by the colonial British, forced an alliance with the old and new rural poor to contest the new regime. Though their interest were divergent, the enemy for both classes was the same-colonialism. Thus, class alliances became more common just as class conflict rose as well. And this process affected the folk religious sects and groups too, as everyone grappled with coping with turmoil.

This turmoil produced more inter-class social and cultural tensions and proximity between the two wildly divergent groups. One such group was the Baul community of rural Bengal.

From Shadows to Scrutiny

The theological structure of the Bauls is drawn from multiple formal and informal religious sources. They range from pre-organised animist practices to ideas of formal religions as perceived by non-literate rural populations. This included North Indian Hinduism, such as 15th century Vaishnavism (Gaudia), Tantricism, both Hindu and Buddhist streams, and folk Sufi Islam influences, not to mention Nathism and Shahjiya beliefs, which themselves were mixed belief clusters. In other words, religious ideas from all sources were mixed with Baul ideas.

Bauls, like all folk sects, are fundamentally informal, which allows them to mix various beliefs that help villages cope with life and reject what oppresses them, like caste and class structures. Its syncretism is a product of this fluidity. It’s ready to adopt and add as it moves along, and though some have claimed it has dates, names and address of its founders, most scholars think it’s a product of a process, not an event.

“Baulism” is a very fluid process owned by people who are not just non-literate but also socio-economically marginalised. Not many of the rural marginalised and denied became Bauls. Still, they empathised with their notions of “humanity and love” and rejection of the formal religious practices that were oppressive to them. From that angle, the sturdiest and long-term adherents of Bauls are the villagers who kept it alive because it mattered to them before the socio-economic elite started to pay attention to this movement.

The Bauls, who rejected most mainstream religious norms, drew in men and women who were shunned from society for a variety of reasons, be it for disease, disability or suffering from disillusionment with the established socio-religious culture of the period. Although many left their village homes and became wandering minstrels, Bauls remain a deeply knit community. Although without a formal “home”, their gathering place, the Akhras became a sort of “home to the Bauls.

Although informal, certain aspects of the Baul belief structure sought to develop ideas of formal salvation around the Body (Deho) as the destination of the journey to the Divine. However, this journey cannot be undertaken alone. The new entrant must be led by the Guru (master), and this is critical. Thus, while Bauls are informal and isolated from social norms and society, they are more structured within themselves.

The seeker is led to the Divine guided by a Guru in his Akhra with other disciples who are part of the same calling. Even when a Baul moves on from his Guru after graduation, it is with the Guru’s blessings and to create an Akhra and a community of his own.

Lalon’s Journey

Baul Lalon’s history, including after his death, shows that three groups had walked with him on this path from the beginning. The first were the ordinary villagers who took care of him, saved his life, and introduced him to the Baul culture. The second was the Guru and his other disciples, who together form the somewhat secretive Baul community that initiated him to the ways of their practices. And finally, we see the educated and often urban elites who interacted with Bauls and, upon being impressed, spread the word to Bengal and beyond.

As a Baul, Lalon spoke very little of his past. He had even mentioned to Jyotinindronath Tagore that he had two births already. The first was when he was infected by smallpox and left to die by his family, but was saved by Matijan and her husband. His second life began after that.

When Lalon had returned to his own family after recovering from his illness, his mother and wife both rejected him due to committing “onno pap” or the “sin of food” by sharing food at a Muslim home, a common taboo of the era. He then returned to Kushtia, where he is supposed to have met Siraj Sai, his Guru. Siraj was a Sufi Baul, a palanquin bearer by profession. And his new journey began.

Not much is known about Siraj Sain, and some scholars even deny his existence, but going by Baul theology, the Guru is the critical factor in turning an acolyte into a sadhu, so Lalon must have had one. So there appears to be no reason to make up this story, but then, such stories and speculations are familiar about him and the Bauls.

Siraj is a constant presence in his songs, and his name is etched together with that of Lalon Shah as the guru who made him who he became. It was the most important person with whom he interacted and walked him to the door through which he could enter and seek enlightenment, the Baul way.

After the death of his Guru, Lalon began to accept disciples and set up his own Akhra. The land on which it was set up was gifted by an admirer, and it fell under the zamindari of the Tagore family, who took a keen interest in him. It is through the attention of the Tagore family, particularly Rabindranath Tagore himself, that Lalon began to become a person beyond the borders of Kushtia and ultimately reached the global knowledge space.

With Him within the Community

Like Bauls before him, Lalon did not write down his songs as the Baul culture is oral, which is suitable for a non-literate society. His music was transcribed and promoted by his disciples and admirers, mainly after his death. They were also mostly illiterate. Among the few who could read and write, Moniruddin Shah and Bholai Shah are credited with writing down most of Lalon’s work.

Kangal Harinath, an admirer of Lalon who set up a music group called Fikir Chand to popularise Lalon’s songs, played a significant role in popularising and preserving his songs. It’s generally believed that Lalon might have written, in his very long life, around 800 songs. Other numbers circulate.

It is safe to assume that the version of his songs that survive have been edited by those who survive him to translate the songs into the standard dialect for legibility (Khan). Many of Lalon’s disciples, including Moniruddin Shah and Bholai Shah, took on disciples of their own after Lalon’s passing and continued to carry his influence forward even after centuries.

Other names that come up are Shital Shah, Bholai Shah, Panchu Shah, Malom Shah, Manik Shah, and Muniruddin Shah. Some were later Bauls who kept contact with the Tagore family.

According to experts, Lalon’s direct disciple, Fakir Manik Shah, first attempted to give a tune to the verses, which the Bauls called Kalams. They were verses reflecting the discourse of Ohedaniat. Fakir Maniruddin Shah and his disciple, Fakir Khoda Baksh Shah, also did the same. Khoda Baksh’s disciple, Amulya Shah, with a reputation as a musician, set Baul songs, especially Lalon songs, to music. His disciples further developed these songs. The tradition continues.

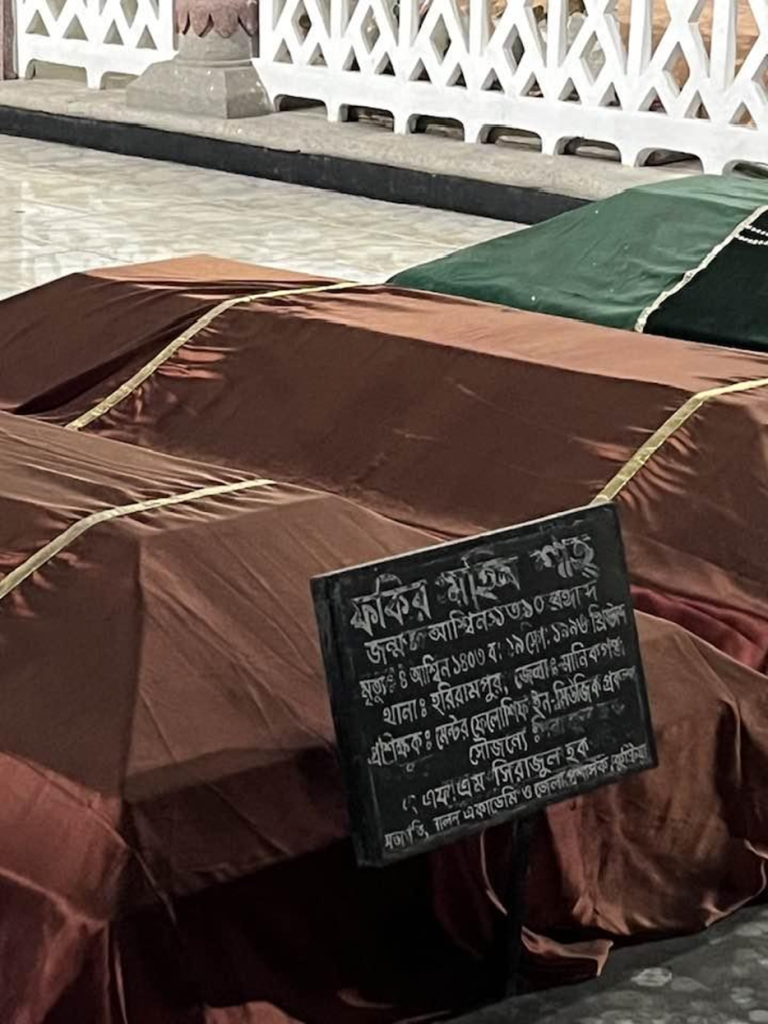

Caption: One of the Fakirs buried near Lalon who would never have seen him

Beyond the Community

Baul culture drew the attention of the Bengali intelligentsia towards the end of the 19th century. In this, the Tagore family played a significant role. A nice of Tagore Sorola Debi first mentioned his songs and those of another folk icon, Gogon Harkara, in the Bharati magazine published by the Tagore family.

Before this point, the Baul tradition, though liked and admired by the locals, had been a strictly oral one, passed down from Guru to disciples and so on. Another reason for their relatively secretive nature was sexual practices, which formed part of their spiritual world, according to them, which would have been very controversial to the broader world.

But this didn’t apply to their songs, which were publicly performed in many cases and whose meanings had a much more universal appeal, going beyond the community.

It’s at this point that the socio-politically weakening upper class of Kolkata, facing rural unrest and political disturbance in urban zones, sought new imaginations, including in rural cultures or indigenous cultures. And it’s here that the Tagore’s, particularly Rabindranath, played a significant role in connecting with the Bauls.

Tagore was not only impressed by their philosophy of humanism but also by their songs as well. He adopted several such songs to his own and made them popular, often making adjustments. His most successful work is, of course the national anthem of Bangladesh based on a Baul tune.

As colonial politics grew more complex and Tagore felt under pressure by socio-political conflicts, he turned to the Baul message of ‘humanity for all” as a route to social harmony. He also preserved their manuscripts, making a very significant contribution to sustaining Baul culture.

And when the Nobel laureate in his Hillbert speech mentioned Lalon in his discussion on Human religion, Bauls/Lalon did become a global issue for discussion in the world of ideas.

Author

Joutha Monisha