Lalon Shah, arguably the most celebrated Baul of all time, by blending different traditions of devotional rights such as Sufism of Islam with Shahjia of Buddhism and Vaishnavism along with many other traditional beliefs, were able to raise some universal questions in simple words through his verses. The preservation of the authentic lyrics and tunes of Lalon songs has become a hot topic after traditional Baul songs of Bangladesh have been proclaimed as one of the 43 masterpieces of oral and intangible world heritage by UNESCO. Even 135 years after Lalon’s death, his songs require appropriate attention, verification of authenticity and preservation through government, NGOs, corporates and individuals.

The aspects of the first documentation of Lalon’s songs followed by methods and key figures who contributed to their preservation is a matter of intrigue. Also, the current locations of Lalon’s authentic manuscripts and archives along with the debates and controversies which surround Lalon and his songs are topics which interests people who is acquainted with Lalon’s work.

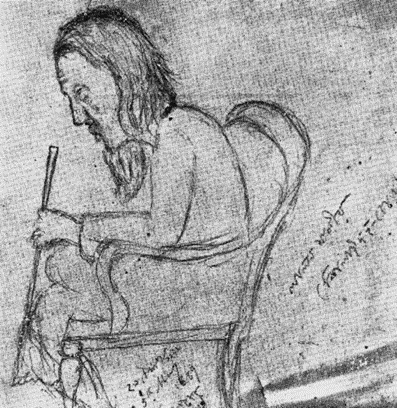

(Portrait By Jyotirindranath Tagore)

The portrait below is sketched around 1884 by Jyotirindranath Tagore, elder brother of Rabindranath Tagore, which is the only surviving authentic portrait of Lalon which gives the world the opportunity to imagine the image of this mystical figure not only as the person but also as the inspired Baul.

First Documentation of Lalon’s Songs

Lalon did not write down his own songs. His songs were rather transcribed by his admirers and disciples, mostly after his death. Moniruddin Shah and Bholai Shah, were one of the very few literate Lalon followers who are credited for penning most of Lalon’s work. Also, Lalon’s verses have mostly been documented by one of his close friends and associates Kangal Harinath, Mohammed Monsuruddin and Rabindranath Tagore with some deliberate distortions to the lyrics. Interestingly, it was Sarala Devi Choudhurani, the elder sister of Rabindranath Tagore, who first collected a few songs of Lalon which were published in their family run newspaper Bharati after Rabindranath Tagore was being touched by Lalon’s work. Quite early,Tagore published 298 of Lalon’s songs in Prabashi. It was Tagore’s transcriptions of Lalon’s songs that introduced his ideas to the Bengali literary canon and attracted the initial interest of scholars in his work.

Methods of Preservation of Lalon’s Songs

Lalon’s songs, known as Lalon Geeti has been initially transmitted through oral tradition method, where Lalon’s verses (also addressed as Kalaams by the members of Ohedaniat cult ) often got transferred orally from baul to baul followed by the transcription method of songs by Tagore and others followed by publications of his song collections in printed ontologies and journals (Choudhury, 2002 ). Moreover, Bangla Academy and cultural ministry is digitizing lyrics, recordings and manuscripts to preserve them whereas performances at Lalon Akhras and events like Lalon Melas keep the tradition of Lalon’s songs alive and plays a role in its preservation.

Key Figures in the Preservation of Lalon’s Songs

Rabindranath Tagore initially systematically documented and discussed Lalon’s philosophy and popularized it among Bengali intelligentsia and others. In 1341 BS, Rabindranath Tagore, in his written speech in Chhanda (prosody) in Calcutta University, highlighted the prosody of three songs of Lalon. Additionally, in his lectures like ‘A Religion of Man’ (1930) at Oxford University, ‘An Indian Religion’ in France, along with the preface of Mansuruddin’s book titled Haramoni (Poush 1334), Tagore explained different philosophical messages and aspects of religion with quotations of Lalon’s songs. These efforts introduced Lalon to the educated class both at home and abroad. Kazi Nazrul Islam was also another key figure in the preservation of Lalon’s songs after being inspired by Lalon’s revolutionary spirit (Hasan) and promoting Lalon’s folk spiritualism by referring to those ideals in his poetry.

Fakir Anwar Hossain, popularly known as Lalon devotee Mantu Shah preserved authentic lyrics of Lalon songs in the three volumes of his book titled Lalon Sangeet by using the manuscripts of Maniruddin Shah; a directed discipline of Lalon whom Lalon himself authorized to pen down his verses. Who instructed Mantu Shah to preserve Lalon’s work was his guru Kokil Shah. It was the instruction and inspiration of Mantu Shah’s guru that led him to work extensively to collect Lalon’s verses since 1960, travelling across India and Bangladesh. He is mentioned to have taken help from a few people throughout this journey of preservation of Lalon’s work, including Fakirs such as Abdul Gani Shah (Bader Shah), Abdul Karim Shah, Durlav Shah and Bazlur Rahman Shah. Mantu Shah further urged about the necessity of the government to collect and preserve the manuscripts of Maniruddin Shah from the personal collections and called for more Lalon verses publication to avoid debates around their authenticity.

Then, scholars such as Sunil Gangopadhyay wrote essays reflecting on Baul influence in Bengali thought. Added to that, folk music collector and performer, who was immensely popular in both East and West Pakistan archived Lalon’s songs (Ahmed) and Shukumar Ray chronicled aspects of relevant folk life and culture of Bauls. Consequently, Researcher Anwarul Karim ( 2010) published on Lalon’s impact and ideology whereas Dr. Fakrul Alam studied Lalon’s place in Bengali intellectual tradition. The influential contemporary Lalon scholar Dr. Abdul Ahsan Choudhury compiled and edited Lalon’s songs’ lyrics (2002) after intensive study. Also, Bangla Academy has been putting institutional efforts to publish, archive and study works of Lalon and Lalon Academy in Kushtia is trying to promote the legacy of his songs through publications and festivals like Dol Purnima which contributes to the preservation of Lalon’s songs through communal effort.

Current Location of Manuscripts and Archives

Few original manuscripts of Lalon remain in existence due to the oral nature of generational Baul transmission tradition but these transcribed versions are housed in several locations across Bangladesh and India. Early transcriptions and notes by Tagore are in Rabindra Bharati University Archives in Kolkata. Many edited and published versions of Lalon’s songs can be found in Dhaka’s Bangla Academy. Added to that, The National Library of Bangladesh holds archives of some published and scholarly collections of Lalon’s work and songs and the Dhaka University Libraries are home to many thesis and research articles on Lalon. Dr. Abul Ahsan Choudhury immensely praised the efforts of Mantu Shah for locating 20 manuscripts in the personal collection of scholars, Fakirs and common people across India and Bangladesh. Consequently, custodian of manuscripts, oral recordings of Lalon songs and cultural exhibitions are present at Lalon Academy situated in Cheuriya, Kushtia, Bangladesh.

Debates and Controversies

Certain levels of controversy and debates surround most of the research work done on Lalon. A controversial aspect of Lalon is the biographical informational discrepancies which became amplified as 19th century Bauls such as Lalon intentionally kept it minimal, private and ambiguous. Another controversial aspect of Lalon is about his religion which had its roots in the Pakistani period where few scholars wanted to label him as Muslim. Studies suggest that Lalon was never open about his religious background even to his closest associates. He was neither a Muslim or Hindu. On the contrary, he opposed any form of institutionalized religion in his songs except humanism and developed a doctrine called Ohedaniat combining traditions and religious rites and customs of Buddhism, Vaishnavism, Sufism along with other religions. The devotees of Ohedaniat call Lalon’s verses Kalaams where Lalon interpreted dehotatwa (going beyond physical state to metaphysical) in his own ways where the songs convey deeper philosophy of the human body being the seat of all truth.

Another serious controversial issue further revolves around the correct number of preserved authentic Lalon songs which are compositions by Lalon Shah himself. Rural Bauls claim the number to be up to 10,000 whereas seasoned Lalon devotees including Fakir Bader Shah and Mantu Shah mentioned it to be just around 2000. The addition of many songs of other known and lesser known Bauls such as Gopal Shah, Adam Chan, Sati Mayer Ghar followers and Indian pseudo Bauls as Lalon Geeti to gain more reach imposes a serious challenge to verify the authenticity and number of actual Lalon songs accurately. Also, any song containing the phrase ‘Lalon Bole’ are not composed by Lalon but other Bauls who imitated his style to popularize these songs to wider audience, but the underlying philosophical messages of these songs are very different from Lalon’s. Researchers only consider about 800 Lalon songs preserved and documented by Tagore and Mantu Shah are considered the most authentic Lalon Geetis with minimal controversy.

Apart from the meaning of the lyrics, debates shroud even the authenticity of Lalon Geeti tunes. Verses of Lalon have been given music by generations of his disciples among who musicologist Amulya Shah played the most important role. The three presently existing familiar tunes of Lalon songs in Bangladesh are derived from Akhrai tradition, blending of Akhrai tradition and classical music ( e.g. Farida Parveen’s Lalon songs where she claims to emphasize on the classical aspect of Lalon Geeti which is different from that of Akhara due to its added polished form) and the fusion of western music with Akhrai tradition done by few contemporary bands and Farida Parveen strongly critiques these band adaptations of Lalon Geeti and calls them nothing but pieces creating ‘confusion’. Also, Lalon researchers have challenged the use of classical instruments such as Harmonium or Bansi with Lalon Geeti but advocates the usage of Ektara, Dotara, Baya and Khamak, used by Khadaboksho Shain, Mohshed Ali Shain and other Lalon exponents in the rendition process of Lalon’s songs.

Consequently, disputes exist between Bangladesh and India over the cultural custodianship of Lalon’s heritage (Karim, 2010), and debates surround organizations and entities involved in verifying and promoting the preservation and cultural practices of Lalon’s songs, archives, manuscripts. Lalon Loko Shahitya Kendra was founded in 1963 for authentic preservation of Lalon’s songs, music and research work followed by the formation of Lalon Academy in 1978 with the same intention followed by the allocation and spending of 4.49 crore Taka by Ministry of Cultural Affairs on Lalon Academy Complex at Lalon’s shrine, and all these initiatives only benefited fewer influential locals or small group financially without contributing much to preservation of Lalon’s work, philosophy and protection of his actual followers who are barred from the Lalon’s Shrine unfairly although the Supreme Court of Bangladesh gave these devotees the verdict to be there. Also, performers are paid very little or no money for their songs in cultural events although they get a lot of foreign and government funds along individual donations which gives rise to a lot of debates. Hence, experts on Lalon see these preservation investments of the Lalon Shrine and Complex as nothing but a waste of money and resources as these go into individual pockets of influential people instead of adding to the cause.

The preservation of Lalon’s songs is not just a matter of cultural heritage but a reflection of Bengal’s spiritual and philosophical history. While the oral tradition has kept his music alive, scholarly and institutional efforts are essential in protecting and propagating his teachings. Future endeavors must focus on preserving the integrity of Lalon’s vision while adapting to modern archival standards. Although we live in a capitalist society and free market economy where treating Lalon’s brand as a profitable commodity along with fusion of tunes, lyrics and styles of Lalon’s songs with diluted philosophical value seems inevitable, but efforts of at least a small group striving to preserve the integrity and authenticity of Lalon’s institutional structures, songs, manuscripts and contributing to the cultural practices and further research around Lalon, etc. is extremely necessary for the protection of our intangible cultural heritage and history.

Author

Shanchary Kader Orpa